At the top of my last piece, I mentioned that I was engaging in a crowdfunding effort for a Ghazzawi family. I have been in communication with Khalil Zeyara, and about a handful of us are putting our collective efforts into boosting his campaign and the campaigns of many other families in need. We have seen movement in Khalil’s campaign, but it is many tens of thousands away from the goal. Since October, Khalil has been actively posting and sharing stories and building his social media savvy, but it is not enough. He needs more people of conscience to step up and help support him. You can do that by donating to his GoFundMe, buying a print from my shop, or pooling funds with friends to maximize impact. Like many other Palestinians, Khalil’s GoFundMe started as an evacuation fund. Still, in the hundred days since the Rafah Crossing closed, his campaign has become a fund for his family to buy necessities from food and water to tents and medical care. I have started both posts this month with a note about Khalil because crowdfunding campaigns require many different strategies and many hours of scheming, which has trickled into this platform. If all 529 of my subscribers sent $5 to Khalil, we could raise $2,645. If all my subscribers sent $10, we could raise $5,290. A they/them can dream!

“Mutual aid projects are a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions not through symbolic acts or putting pressure on representatives, but by actually building new social relations that are more survivable.” - Dean Spade

Mutual aid mobilizes people, expands solidarity, and helps build critical movement infrastructure. Mutual aid is participatory; it allows us to solve problems through collective action rather than waiting for so-called saviors. Mutual aid is “we take care of us” personified; it is a practice of good governance. It is solidarity manifest, connecting our praxis with tangible actions. Mutual aid is survival work.

Donating to crowdfunding efforts may not count as mutual aid, but it is direct, necessary aid. Over the last ten months, many efforts have been made to raise funds for more prominent organizations and nonprofits, but the aid has not reached all Palestinians across the Gaza Strip. The physical and psychological torture caused by food scarcity, lack of protection from rains, excess heat and cold, electricity, water, and the loss of many other resources has driven these people to gather more than they need, leaving others without any resources at all. The conditions were different, but this is the type of resource hoarding we saw when the pandemic kicked off in 2019; despite the various ways it manifests, the systemic consequences of capitalism are felt and replicated worldwide, whether in times of pandemics or genocides.

Donating directly to families’ GoFundMe appeals helps the most because almost all aid sent by organizations is taken and sold for profit by zionist occupiers or a small group of merchants who are desperately making money for their survival. People with fewer resources are forced to buy things they need at an extremely high markup, so high that most can't afford them. For reference, inflation prices mean that one tomato costs 10 shekels or USD 2.73, 7 bell peppers cost 120 or USD 32.79, and two pounds of eggplants cost 50 or USD 13. Very little meat is available for families to eat, and they have mostly been sustaining themselves on things like canned food, flour, lentils, or in starved parts of Gaza, boiled grass and animal feed. $10 directly given to a person in need is guaranteed to help that person much more than giving to any nonprofit or charity. People are dying and starving while the wealthy capitalists hoard and the occupiers sabotage any aid from going into Gaza or kill people who are desperately waiting for food and water as they have done in several “flour massacres.” These are the hidden costs of the American-Zionist genocide and blockade that is forcibly starving Palestinians.

It is not normal for families to be begging for people to pay attention to their needs on the internet while they are fleeing bombs, fire belts, starvation and dehydration, disease, and many more horrors we cannot comprehend.

Kamala Harris's campaign raised $80 million in one day and over $200 million since announcing her takeover of the Democratic ticket. How many Palestinian, Darfuri, or Indigenous families could have met their crowdfunding goals with that money? How many of them could afford to support themselves and their neighbors? How many of them could have saved that money to evacuate when the time comes? And if your focus is on the local level, think about our houseless neighbors, seniors who are living out of cars, students who can’t buy food, refugees who are attacked by the police for selling snacks – think about how their material needs could have been addressed with that level of fundraising. Clearly, I’m still not over it.

The ills of this world are reflected back at us in those who fall on hard times. Do we ignore them to pretend it isn’t happening? It breaks my heart that so many people are more motivated by electoral theater and not the plight of regular people. Are we selfishly compartmentalizing the things we see and experience firsthand?

“I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they don’t think I’m human… And this means that they have become, in themselves, moral monsters.” James Baldwin

I don’t want anyone to misunderstand me; I am not approaching these critiques motivated by some holier-than-thou attitude. One of the things I’ve been navigating as a late AuDHD-diagnosed person is this idea of “justice sensitivity,” which is described as the tendency to notice and identify wrong-doing and injustice and have intense cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions to that injustice. Over the years, I’ve been called too sensitive, and now that I know where it comes from, I understand I am not the problem. Our society is so damaged, with values and standards that are not crafted for all of us. I also wish I didn’t have to name my disability every time I offer a critique that may piss people off or make them uncomfortable – folks either infantilize me or take their mother wounds out on me. Exposing myself to their internalized ableism feels like a lose-lose, but if I stop speaking truth to power with the little bit of energy and resources I have, I will experience soul death.

I want us to reject this myth that every oppressed group has to wait their proverbial turn for liberation before fighting for another. In hoisting up these myths as truths, we are saying that for us to live, others have to die. If that’s the case, what kind of world are we living in, and is that world worth saving? I want to believe in the overwhelming possibility of mutuality.

Mutual aid became part of the collective revolutionary consciousness thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. We need to bring back the same energy, work towards systematizing it, and see ourselves as part of a culture of mutuality. For some reading on mutuality as a framework in the so-called “post-pandemic” era, read Marina Gorbis’s piece, Post-Pandemic Transformation: Building a Mutualist Future (10-minute read). Gorbis walks through mutualism and recommends how to flip our ideological switches from individualism to interdependence, exploitation to stewardship, commodities to universal rights, and scaling up towards resilience.

There are ecosystems of care that exist, yes. Still, so much of the idea of care is feminized labor or viewed as a core part of liberation work, which shows how deep settler colonialism and unfettered capitalism have erased centuries of decolonial struggle against empire. Lest we forget that mutual aid is an unbroken tradition among Indigenous people, maintained through traditional teachings that contemporary aid projects are working to restore. Settlers have long worked to undermine Indigenous people’s self-sustaining practices by first destroying food systems and then forcing dependency on rations given at forts by missionaries and by settler nonprofits today. Indigenous mutual aid efforts are both a matter of survival and resistance to forced dependence on settler systems. Diné organizers Kauy Bahe, Radmilla Cody, and Brandon Benallie conceptualized mutual aid with the term k’é. This Navajo kinship system asserts that the entire universe is connected through a careful balance of reciprocity that must be intentionally maintained. K’é includes love, compassion, kindness, friendliness, generosity, and peace as components of all solidarity work.

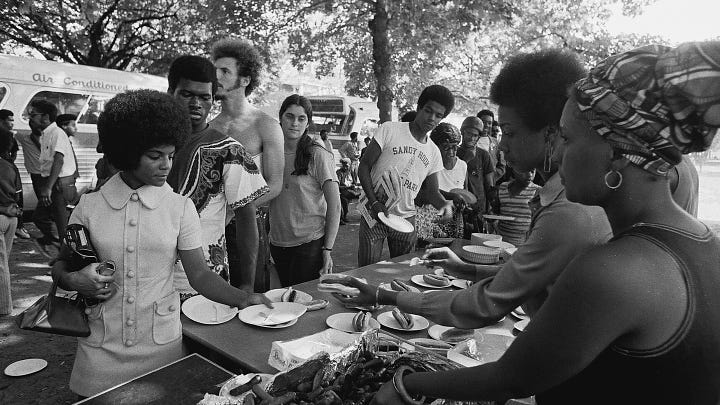

And, of course, this wouldn’t be a proper Comunicado without some historical throwbacks, so here are a few examples of mutual aid and collective care:

Philadelphia experienced a yellow fever epidemic in the summer of 1787. Richard Allen and Absalom Jones started the Free African Society, one of the country's first Black mutual aid societies. Members of the Free African Society offered relief to the sick, sheltered orphans, and buried the dead. They used small membership fees to create a communal pot of money. The FAS became the blueprint for Black mutual aid societies in the 1800s, springing 100 of these societies in Philadelphia alone!

One of the mutual aid societies inspired by the Free African Society was the New York Committee of Vigilance, established in 1835. When Frederick Douglass escaped enslavement, he fled to New York City and found support in the New York Committee of Vigilance through David Ruggles, an organizer and a conductor on the Underground Railroad. The Committee practiced “practical abolition” in its multiracial membership, who took up arms to confront slave catchers, supported Black folks in court, and provided shelter, food, transportation, and education. While wealthy white folks provided financial resources, Black women members were the face of fundraising, creating bake sales to fuel the Committee’s work.

The Free Breakfast for Children Program (established in 1969) was one of the Black Panther Party’s 60 survival programs. Drawing on research showing that breakfast is an essential meal for health, happiness, and learning, the Panthers began cooking and serving kids in Oakland before expanding to 45 cities across the country. Their expansion relied on donations from neighbors and local businesses.

The Young Lords Garbage Offensive (also circa 1969) got together every Sunday to clean up the trash that the Sanitation department neglected to collect in Harlem. When they didn’t have enough brooms to sweep garbage, they asked the city to provide them. Of course, the city of New York refused, and in protest, the Young Lords swept the trash into the middle of Third Avenue and set it on fire, forcing the city to clean up. The Young Lords were influenced by the Black Panthers and adopted initiatives like building occupations, breakfast and daycare programs, and free healthcare screenings for the community.

Recently celebrating its six-month anniversary, Operation Olive Branch provides support to refugees in Congo, Sudan, and Palestine. This includes evacuation, medical care, housing, electricity and WiFi, and perinatal care. In partnership with on-the-ground organizations and community members, Operation Olive Branch has raised well over a million dollars.

To quote Creators for Gaza, who have raised over one million dollars through concentrated crowdfunding, the only meaningful support to an occupied people is material support. Mutual aid ensures the money will go directly to those in need, it is the most efficient and helpful way to help people access their needs. Remember, the one person or family you are giving funds to is connected to a bigger community of people who are in need too. More often than not, GoFundMe recipients are pooling resources with their neighbors, making it that much more impactful.

Want to move from direct aid to mutual aid? Create or join a group of folks working directly with and alongside Palestinians, Sudanese, or Congolese survivors to create and promote their GoFundMe campaigns, like and share their posts, and get creative with your social media strategies. Run raffles, put together shows, sell artwork, take advantage of viral trends, and create videos that share their stories. You can “adopt” a campaign, meaning you collect funds on their behalf, create shareable graphics, and offer them support. The most rewarding thing is establishing companionship with the folks you are talking to. Take your conversations off Instagram or TikTok and use international SMS apps like WhatsApp.

Here are a few requests that need signal boosting; maybe you can share them on your socials and use some of the approaches I’ve named above and below:

Kalsoom is raising funds to help her brother, sister-in-law and their five children who are currently trapped in Sudan get to their family in Pakistan. Their situation is very critical, since Kalsoom’s sister-in-law is three months pregnant. They need to raise $4,000 by August 25th.

Asjad and her family are in the process of getting their passports and have left Khartoum towards northern Sudan, and they are only $2k shy of their total goal to escape to Egypt. It would be fantastic if they could close the gap before the month is out.

Ebaa is an artist and graphic designer from Deir al-Balah and despite the ongoing genocide, she is offering high-quality drawings to fund her survival. Check out her Instagram page and consider supporting her as she cares for her family, including her sister Shaima who has been struggling with a lack of medical attention for her diabetes.

And here are some quick tips for social media engagement:

Post comments that are 9 words or longer. Do not include political or censored words like genocide, doing this will help the algorithm boost the post.

Emojis don’t count towards the 9-word limit. As a form of engagement, try to add a comment that is directly related to the video or post. The predictive text is fine, but it is not always helpful.

If you don’t know what to write, you can rant about your favorite things (except food, I don’t know why).

When sharing mutual aid posts, share the link as a hyperlink whenever possible.

When sharing stories on Instagram, add at least two features, like music and a poll, and explain why the cause is important to you in your own words.

One-time donations are helpful, but long-term, consistent support is crucial. Can you skip your morning coffee once a week? Can you skip a round of drinks at the bar with your friends? Do you need all of your monthly subscription services? Can you instead reroute that money to help families in need to stay alive? You can set a recurring monthly calendar reminder to donate the cost of that coffee, drinks, or monthly subscription service to donate to the fundraiser of your choosing. You can also ask your friends and family to do the same; take a WhatsApp auntie/susu approach and forward the campaign of your choosing to 10 people, asking them to do the same.

Before I close this out, I want to shout out Palestine Asdiqa, Workshops4Gaza and Lisa, Operation Olive Branch, Palestine Solidarity Action Network, Pocket Change Pools, Queer Asians 4 Gaza, Dahnoun Mutual Aid, Creators for Gaza, Build Palestine, OOB, and organizers like Elizabeth Xu Tang, Yejin Lee, Tai S.. Their work helped inform this piece, and I recommend you follow them and put in some elbow grease by volunteering!

“So long as mutual aid remains an anarchic form of praxis, it avoids many of the pitfalls of revolutionary movements that depend on charismatic leadership, strict adherence to an ideological framework, or purity politics that alienate and confine multiplicitious personalities, perspectives, and possibilities for living. Mutual aid, as praxis, is neither a doctrine nor a discipline, but a radical orientation toward living with and struggling alongside others in an ever-changing world.” - Jennifer Gammage